When was the last time a work of literature changed your life? I mean, the day after you finished it—or even the same day—you were inspired to go out and do something, or to stop doing something. And again, I’m talking about literature. Not a self-help “7 Habits of Highly Effective etc.” or a guide to quitting smoking, or a non-fiction book about what goes into a chicken McNugget. Nor a simple children’s fable with a simple moral, like “The Ant and the Grasshopper” or “The Tortoise and the Hare.” I’m not talking about religious tracts, either. While the Quran and the Bible can certainly be read as literature, dogmatic religious instruction usually veers either toward the blindingly common-sensical (Thou Shalt Not Kill) or to the laughably arcane and archaic (If there is a man who lies with a menstruous woman and uncovers her nakedness, he has laid bare her flow, and she has exposed the flow of her blood; thus both of them shall be cut off from among their people. –Leviticus 20:18)

The truth is, while literature can and often does better us, it’s seldom in a direct “go out and do this” kind of way. The process is more complex, deeply-rooted, and mysterious. Literature works on us by stirring and stoking empathy, enriching our inner-lives, and making us more mindful and contemplative. Literature makes us feel more connected to others (again, empathy), allows us to better know and understand our own hearts and minds, and draws us into moral debates (rather than delivering simple moral pronouncements) that help us toward becoming better people.

Are people who read literature better people than those who don’t? No, it’s not so. The world is full of saintly illiterates and well-read monsters. Consider the example of Ieng Thirith, the sister-in-law of Pol Pot who just died on August 22nd. She was key collaborator in the Cambodian genocide and only avoided trial by UN Tribunal due to dementia. What kind of education led her to willingly participate in the Khmer Rouge’s experiment in mass misery? Why, only a degree from the Sorbonne in Shakespeare studies! Or read the chilling essay “The Book of My Life” by Bosnian writer Aleksandar Hemon, about his favorite literature professor from the University of Sarajevo, a warm, humane, incredibly well-read man who ended up becoming a high-ranking member of the Serbian Democratic Party and basically the right-hand man of Radovan Karadzic, the savage Serbian nationalist who ended up becoming the most-wanted war-criminal of the 1990s. For some, all the literature in the world can’t drum up a dime’s worth of empathy.

And yet I would argue that literature does provide some kind of map of the minefield of life, some fortification of the soul’s ramparts. It’s a cliché to say that great art “elevates” you, but in a sense, it’s an accurate verb, because reading a great work of literature does make you feel lifted, almost like an out-of-body experience, like you’re being lifted into a better version of yourself.

However, (long-winded introduction finally coming to an end, now) this essay isn’t about that complex, nuanced, intangible kind of betterment. It’s about the first, more direct kind. It’s about a recent reading moment that, in a small but tangible way, stopped me from being an asshole. Or as much of an asshole.

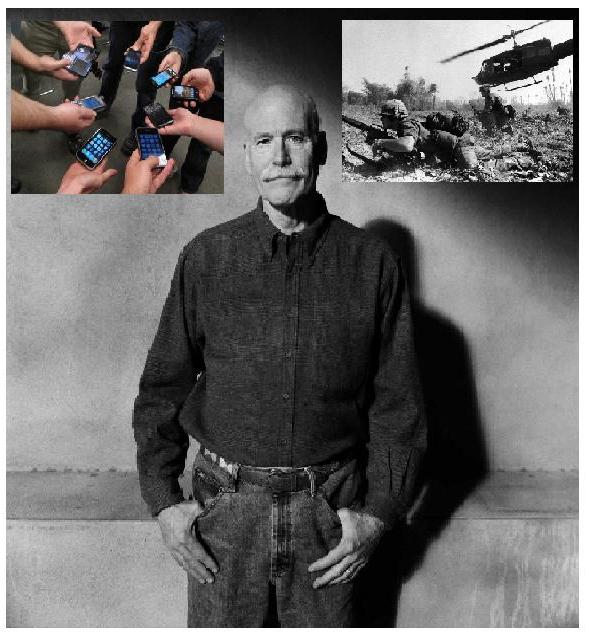

How often does this happen to you: you’re walking down the street, and a guy with eyes glued to his new Galaxy S6 smartphone barges into you. Maybe you weren’t quite looking where you were going either—maybe you had your eyes on your own smartphone, facebooking, ka-talking, whatever-ing. Maybe you were just deep in thought or had your eyes on a pretty girl across the street, but for whatever reason, you didn’t see the guy, and there’s a mini-collision. Maybe one of you drops your phone and the battery pops out, or, horror-of-horrors, the screen cracks. Tough titty, pal. Watch where you’re going.

Now, has THIS ever happened—you actually see the guy coming at you, you know he’s engrossed in his 3G unlimited-data world, you see he’s heading straight for you, but you do nothing to avert the collision. Fuck it, you think. I’m entitled to my clearly-established direction of movement. I’m the one playing by the rules—looking where I’m going. So . . . you let the guy plow into you. Or you just plow into him. Intentionally. Maybe sometimes, as you see head-down guy coming at you, you stop dead, becoming a fence-post, a human pylon, making it even more embarrassing for the guy who isn’t looking. Contact is made, and you feed him an icy stare that says, hey friend-o, I was just STANDING here, so it’s CLEARLY and TOTALLY your fault.

Psychologists have technical term for this—it’s called “being a total spiteful dick.” And I wish to come clean—I have engaged in said dickishness, not extremely often, but not totally infrequently, either. Nobody really likes getting jostled, shoved and bumped in public, and there’s nothing wrong with holding your own space on a crowded subway and shoving back when necessary. And yes, if you are trying to walk and play Candy Goddamn Crush at the same time, a pox on you. But Jesus Lord, what sort of righteous idiocy is it for me to not simply get out of the way? Now, mind you, I have never intentionally moved into the path of the on-coming no-lookists. There is a difference between being a dick and being evil. That’s a line I haven’t crossed. But it’s still plenty bad to give somebody an entirely avoidable thump just to make my smug point. What do I think I’m accomplishing? Is this guy going to actually learn his lesson and watch where he’s going? Maybe, for the next 30 minutes. Hell, maybe permanently. Who the hell cares either way? Why not just accept phone-blind strollers as another minor, itchy bug bite on the wondrous Body Electric of our modern age of miracles?

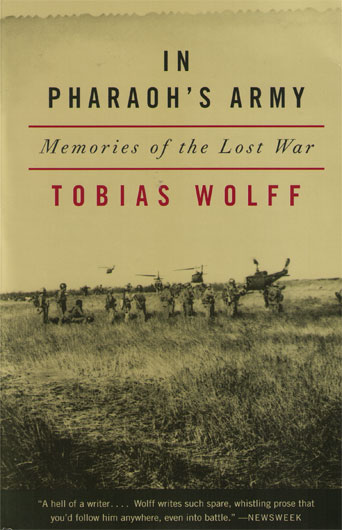

Enter Tobias Wolff.

Tobias Wolff is a contemporary American writer. Although he isn’t a household name on the order of Cormac McCarthy or Toni Morrison, he is still a total heavyweight who has enjoyed popular success and critical respect. He is probably best known for This Boy’s Life, a memoir of his adolescence which was made into a movie starring a young Leonardo Dicaprio and Robert De Niro. The bulk of his work is in the short story genre. He has several collections, all of which are excellent, and there’s a sort of “Greatest Hits” called Our Story Begins which I’ve taught in high school English classes. His stories have regularly appeared in the high-echelon venues for fiction—The New Yorker, Harper’s, Atlantic Monthly, Esquire, etc. He’s getting up there in age (70) but he’s still writing and he still teaches at Stanford University.

Wolff’s short stories are almost all contemporary slice-of-life tales which usually present their climaxes in the form of subtle ephiphanies—flashes of understanding in their main characters’ consciousnesses that they have crossed points-of-no-return in their lives, either for good or for ill. In that sense, he gets grouped with short story contemporaries like Raymond Carver and Ann Beattie. But what sets Wolff apart is his pervasive tone of dark, comic irony as well as the much more active authorial insight we have into his characters’ thoughts, either directly in the 1st person or through 3rd person omniscient commentary (see the devastating last line in the masterpiece “Hunters in the Snow.”) Wolff expertly slices apart and lays bare his characters’ foolish pretensions, arrogance, and hubris with scalpel-like precision.

In this passage from In Pharaoh’s Army, an army cadet in basic training observes the sad-sacks who regularly get reamed out by the drill sergeants for falling behind in marches and drills. At first, he hangs back with them and urges them on in soldierly camaraderie. However, he soon realizes his “band of brothers” spirit has its limits:

I learned to spot them, and to stay clear of them, and finally to mark my progress by their humiliations. It was a satisfaction that took some getting used to, because I was soft and it contradicted my values, or what I’d thought my values to be. Every man my brother: that was the idea, if you could call it an idea. It was more a kind of attitude that I’d picked up, without struggle or decision, from the movies I saw, the books I read. I’d paid nothing for it and didn’t know what it cost.

It cost too much. If every man was my brother we’d have to hold our lovefest some other time.

Now that is great interior exposition, and it’s vintage Wolff—with grim wryness, he pulls the rug out from under the way we delude ourselves about our own goodness and the purity of our motivations. In Pharaoh’s Army, actually, is non-fiction, and the “I” in the above passage is Wolff himself, in training to become an Army Special Forces lieutenant in the Vietnam War. The book is the greatest 1st person memoir of the Vietnam War I’ve ever read. Tom Bissell, the author of the excellent father-son Vietnam War memoir The Father of All Things, calls In Pharaoh’s Army “so well written it’s almost cruel.”

Now that is great interior exposition, and it’s vintage Wolff—with grim wryness, he pulls the rug out from under the way we delude ourselves about our own goodness and the purity of our motivations. In Pharaoh’s Army, actually, is non-fiction, and the “I” in the above passage is Wolff himself, in training to become an Army Special Forces lieutenant in the Vietnam War. The book is the greatest 1st person memoir of the Vietnam War I’ve ever read. Tom Bissell, the author of the excellent father-son Vietnam War memoir The Father of All Things, calls In Pharaoh’s Army “so well written it’s almost cruel.”

I want to write about a passage from this book that jolted me about as strongly as any passage in literature has ever done.

Lieutenant Wolff is stationed near My Tho, in the Mekong Delta. He is serving as an advisor to a South Vietnamese Army artillery battalion. It’s a cushy post. With the harrowing exception of the Tet Offensive in 1968, Wolff saw little direct action. His main challenge was avoiding ambush in supply runs between the his unit in My Tho and the PX at the American base several miles away, where he would trade fake Vietcong souvenirs for steaks, stereo equipment, and TVs.

With just a few days left in his tour of duty, the Army HQ sends over another officer to take over Wolff’s duties when he leaves, a certain Captain Kale. Wolff describes Kale as a gung-ho, arrogant, ridiculous blow-hard. Kale sizes up Wolff for what he readily admits he is—a lazy, feckless officer with little-to-no leadership ability, but with the good luck to have received a relatively soft post where his incompetence didn’t matter, as the South Vietnamese Army was a thoroughly corrupt, undisciplined fighting force whose members basically ignored any American advisor’s attempt to whip them into shape. Captain Kale, in Wolff’s description,

. . .had a round glistening face as pink as a boiled ham. It was the face of soft little man but in fact he was tall and bulging with muscles. In the odd moments when we were stalled somewhere, waiting for a ride, when [everybody else] found some shade and lay back with their caps over their eyes, Captain Kale knocked out push-ups by the hundred . . . While he worked out he told me how he was going to turn his future battalion into a killer fighting unit, unlike this one, and how it was a good thing I was leaving the army, because if every officer were like me the VC would walk off with the whole country inside a week.

One day, Kale notifies Wolff that division HQ has ordered him to move one of the howitzers, and a big Chinook helicopter will come in to lift and move the gun. Kale wants the helicopter to come in above a courtyard in the populated area where their base is located. Wolff says there isn’t enough open space—the wind from the chopper’s rotors would damage or destroy many of the peasant hooches nearby—and suggests the open roads or fields nearby. They argue about it, and finally Kale puts his foot down: “You are fucking with my shit, Lieutenant. I will not have my shit fucked with.”

The helicopter comes in and Wolff goes over to the base’s radio to guide it in while Kale stays with the gun. The copter pilot says he doesn’t think he has enough room to safely descend, just as Wolff thought. This is the key moment of decision. Wolff realizes clearly that he has been given an “out”—he could tell the pilot to come back in 20 minutes after they move the gun outside the village, and cover his ass by telling Captain Kale that it was the pilot’s decision. However, Wolff goes ahead with Kale’s plan: “I wanted Captain Kale’s will to be entirely fulfilled. I wanted his orders followed to the letter, without emendation or abridgment, so that whatever happened got marked to his account, and to his account alone. I wanted this thing to play itself out to the end. I was burning, I wanted it so much.”

So the Chinook comes in and, just as Wolff had warned against, the rotor-wash lays waste to the flimsy hooches. First roofs are torn off, then walls collapse as the terrified Vietnamese run for their lives. The courtyard is filled with whirling dust and debris. The gun gets hooked up to a sling and the copter departs, leaving Wolff and Kale to survey the scene as the stunned villagers pick through the wreckage to find their belongings. The physical description of the scene is brilliant, as usual. However, it’s Wolff’s withering introspection that imbues the passage with its most singeing fire:

This was my work, this desolation had blown straight from my own heart. I marked the discovery coolly, as if for future study. This was, I understood, something to be remembered, though I had no idea what that would mean. I couldn’t guess how the memory would live on in me, shadowing my sense of entitlement to an inviolable home; touching me, years hence, in my own home, with the certainty that some terrible wing is even now descending, bringing justice.

This passage chilled me with its simplicity and precision. What a brilliant choice of imagery, embodying “fate” or “karma” or “regret” or “justice”—abstractions always at risk of cliché—as a “terrible wing . . . descending.” It’s an eerie, ghostly, haunting image, the idea of something slowly coming at you from above, floating, wafting down in the dark, ready to smother you, violating you in your “inviolable home” with your wife and children and your career. (It also subtly mirrors the imagery of the descending helicopter which destroyed the Vietnamese’ homes.)

Now, none of villagers were killed or even injured (in Wolff’s description). Certainly American soldiers were guilty of much, much worse in Vietnam. A reader might even chuckle at the ridiculous Captain Kale eating his humble pie. But the laughter dies in our throats as Wolff puts it into perspective. The whole incident, without Wolff even directly saying so, becomes a metaphor for the whole war—how we sacrificed people we never knew and only pretended to care about to prove a point about . . . what? Our resolve? Our power? Our prestige? It’s bad enough, especially given how avoidable it all was, how easy it would have been for Wolff to change Kale’s orders. Wolff allows dozens of people’s homes to be destroyed for simple spiteful pride.

Cut to 2015, Busan, South Korea. There’s an American walking the streets who makes it a point to nimbly step around phone-distracted Koreans, or gently warn them with a “jo-shim ha-seyo” or a “shillye hamnida” (“be careful” or “excuse me, please”). Obviously, it’s a bit apples vs. oranges here, both in scale and particulars. The Vietnamese were completely innocent, unknowing pawns in Wolff’s game of “Fuck Captain Kale.” In what used to be my game of “Fuck Mr. Smartphone Zombie,” the only victim was the phone-zombie himself. Still, I can’t help thinking of that torn-apart Vietnamese village, and I think of Wolff, more than 45 years after the fact, still waiting for cosmic payback, that terrible descending wing of justice. Why bring even a quantum of negativity into this world to spitefully prove a point, if it’s so painlessly avoidable?

Right, I know: big fucking deal. Yay me. Wolff himself would be the first to lacerate such self-congradulatory twaddle. He would probably observe that I only barged into people in the first place knowing that Koreans, bumping into a waygook, would be too shocked and embarrassed (and too polite) to muster any indignation against me. Would I do this in America? With a dude bigger than me? Probably not. Definitely not. As Wolff might stay, I stood up and made my point as long as there was no cost whatsoever to be paid for doing so.

Still, I think this is as good example as any of how literature can set us to work on ourselves, at first in small ways, then later on in larger ways, chipping away at vanity and self-delusion, nudging us toward our better angels. Literature is merely a series of black squiggles on a white page, yet with miraculous, incantatory power it creates a canvas on which a simulacrum of life is painted. And that canvas somehow becomes a mirror, as it is we ourselves who are painted. For many years, Tobias Wolff has been holding up such mirrors for us. I hope I can always muster the courage to take a long, brutal gaze, taking honest stock of what’s looking back at me.

st to. My travel companion David, who had sampled betel-chewing last year in Bangladesh, gave the Myanmar version a try, and pronounced it sweeter and overall more pleasant than the Bengalis’ concoction. Expect him to start a “Betel Afficianado” blog soon! After booking a domestic Air Bagan flight from a betel-chewing travel agent, my other travel-mate, fellow Sweet Pickles & Corn scribe Eli Toast, remarked, “For fuck’s sake, how do you expect to be taken seriously as an adult when it looks like you’ve got a whole pack of Twizzlers in your mouth?”

st to. My travel companion David, who had sampled betel-chewing last year in Bangladesh, gave the Myanmar version a try, and pronounced it sweeter and overall more pleasant than the Bengalis’ concoction. Expect him to start a “Betel Afficianado” blog soon! After booking a domestic Air Bagan flight from a betel-chewing travel agent, my other travel-mate, fellow Sweet Pickles & Corn scribe Eli Toast, remarked, “For fuck’s sake, how do you expect to be taken seriously as an adult when it looks like you’ve got a whole pack of Twizzlers in your mouth?”